On Grandpa's Farm

Childhood Reflections of Sunday Afternoons on the Farm

You couldn't find a better miniature world in all of Creation than my grandpa's farm. Though it encompassed only fifty acres outside small-town Auburn, Illinois, it contained within its boundaries a gathered world of epic proportions.

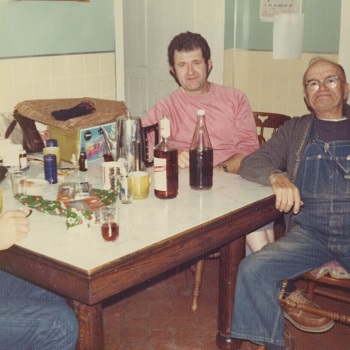

Every Sunday afternoon my dad drove my two brothers and me out to the farm while my mom stayed home with my youngest sisters, who were still babies during my earliest years of romping on the farm. We made the required appearance in Grandma's kitchen before venturing out to the pasture. The practical, no-frills kitchen greeted us with plain Pillsbury cake donuts, black coffee in thick white mugs, and a trusty yellow cardboard box of Domino sugar cubes. Sometimes Grandpa pulled out his homemade wine and shared a sip with the adults. My dad would usually settle behind the wooden, bow-legged table with Grandpa, who nearly always wore blue overhauls and a white Pillsbury cap with a shiny black bill. We kids checked in and scampered out. Even Pillsbury doughnuts were no match for the wonders of the pasture.

Grandpa's pasture opened before us like a new frontier that begged to be explored, even though we explored it every Sunday afternoon. From as soon as we could walk, we learned to spot-check the ground in front of our feet. Pungent cow patties, buzzing with flies, were a requisite part of this world. Once dried, they made good clods for kicking. Knowing the difference made us feel like veterans.

Though we laid claim to the pasture as our own private playground, we knew we were the interlopers. The owners of the cow patties consisted of ten to twenty Black Angus cows, all of which seemed to me like dark, bumbling beasts with a particular intolerance for noisy children. They stared at us, chewing their cud, never smiling.

The pasture covered the space of two football fields. A one-lane gravel road with two dips much like a two-humped camel's back, led from the farmhouse up a slight rise to the white gate—the entryway back into the real world. The gate was usually closed so the cows wouldn't escape into town. It gave us a feeling of being sealed in Grandpa's world.

How can I begin to describe the wonders of that world? Century-old oak trees reached out massive, sheltering arms, dropping acorns and multi-fingered leaves the color of breakfast syrup. As if a park ranger with an aesthetic eye had planted them, the oaks stood mid-pasture in a picnic-like area, overlooking the pond, and along the fence line—enough of them for ample shade without giving the land over to woods.

On dry days, we could descend a little hill to either of the two cement "caves" beneath the gravel road. These twin culverts allowed runoff from the pasture to flow beneath the road, but we used them to watch dragonflies zoom over the goldfish-sized ditches, or, in an emergency, to hide from the cows should they make a hasty appearance.

In the center of the pasture lazed a shallow, mossy pond that served as drinking water for the cows. Its crowning feature was a cement dam Grandpa had built. I still remember the day he proudly showed it to us, as if it were a marvel of engineering, right there in his own pasture. Though the three-foot jump to the bottom seemed a long way for our short legs, we soon found ourselves on the concrete slab behind the dam wall, eye-to-eye with frogs and minnows and dragonflies, and feeling as if we possessed the power of the dam, too. During one of our Sunday afternoon visits, Grandpa used a net to drag tadpoles out of the pond. Dad let us transport them in a bucket to our bathtub for a day, or an hour…just long enough to hold a memory.

One winter, Grandpa tied an old tractor tire on a long rope behind his truck and gave us a ski ride across the snow. On a day equally as hot as the former was cold, he presented us with inner tubes and showed us how to make boats of them (none of us could swim) on the pond in the "back pasture." A Holiday Inn pool it was not. With inner tubes under our arms, we squished barefoot through a roiled concoction of manure and hoof-pocked mud to reach a floatable surface, after which we faced the dangers of crawdads pinching our overhanging toes. But the magic of conquering the adversities thrilled us as we lazed amid the sunshine and whizzing dragonflies.

This back pasture was smaller than the main pasture, which meant it didn't offer as many opportunities for adventure, but I do recall an occasional side trip there. Getting there on foot, though, required walking along a narrow lane between two rusty-wired, weed-choked fences. It reminded me of the long cattle chutes I'd seen on Bonanza and The Big Valley. And the truly intimidating thing about it was—the cattle really used it. If I were unfortunate enough to meet a cow there, I'd be forced to climb the fence with all of its poking wires and hope that I could get over it in time to avoid playing chicken with a cow. Asking a cow to back up in a chute didn't seem like a good plan. I can never remember lingering there.

One of the treasures in the back pasture was a small grove of hickory nut trees nestled in a hollow by the rear fence, where few eyes would ever discover them unless going a-hickory-hunting. We didn't wander back there often, but I recall an afternoon—or maybe two—gathering the white nuggets into wide-mouthed gunny sacks.

Sometimes we transported bushels of walnuts from our house on Walnut Street to Grandpa's farm. Grandpa laid out hundreds of our large, green-hulled walnuts on the ground next to the garage, then drove over them with his tomato-red pickup, loosening the hulls until the pungent scent of walnut oil filled the air with the promise of things grown and gifted. Afterwards, we took those walnuts back home and stored them in barrels for months until the hulls turned black and fell off. When cookie-baking time came around, we cracked the coal-black shells on the garage floor with Dad's hammer, and then sat at the kitchen table with a nut pick and a bowl, gleaning the precious nut-meats for the awaiting cookie dough.

Life brimmed on the farm. There were kittens in the barnyard if you could catch them. Hundreds of red apples fell in the orchard, sometimes fit only for the cows, but sometimes fit for pies when gleaned before they had bruised themselves on moist ground. The gateposts, surrounded by high weeds, cloned four-leaf clovers, and Grandma claimed to have found an occasional five-leaf and six-leaf clover. Once she gave me a large black shiny carved arrowhead from a Velveeta box full of arrowheads she and Grandpa had collected over the years of plowing. That arrowhead is still one of my treasures today.

Of all the adventures on the farm, ice skating was my favorite. We could've skated on the pasture ponds, but they were second fiddle compared to the creek. Sugar Creek flowed along the west edge of the property, beyond a short wire fence that was perpetually bent in a particular spot for explorers like us. Except in flood season, the creek wasn't deep as waterways go—possibly waist-deep—but even in our youth, we were wise to its pitfalls. We knew that fallen limbs meant open water at this jutting elbow or at that protruding fork, especially when trickling water tipped us off. We skirted or climbed each obstacle like modern-day Lewis's and Clark's on an expedition. I had sharp eyes back then.

The creek banks, high enough to block the surrounding fields from view, formed a natural shelter that enclosed us in our own private rink, easily outclassing any Olympic arena. We never followed the creek farther than one or two bends, but we'd heard that it ran all the way to Lake Springfield—nigh 20 miles—and our goal was to skate there. We never did, but we always dreamed of it in the manner of a child who dreams of seeing the world one day.

It would be easy to gloss over Grandpa's farm as if it were a perfect Currier & Ives painting, but the truth is, it wasn't perfect. Every autumn, Grandpa borrowed a bull. On those autumn Sundays, the first question on my lips was always, "Is the bull in the pasture?" Even so, we weren't forbidden from venturing out there, but were merely warned to "keep a close watch out." Those Sundays instilled within me a wary look-over-your-shoulder chill that I still remember today, especially in my nightmares.

Another imperfection was located in a depression near the rear of the main pasture. There, Grandpa dumped old wash machines, engine parts, and bulk trash. Red rainwater collected inside a rusted conglomeration of sharp edges and metal parts. I recall half-hearing complaints from aunts or mothers about the dangers of the gulch, along with recommendations about dumping dirt over it. Once, in the orchard behind the chicken house, we discovered a set of cow bones like a lady's hoop skirt. No one would tell us how the cow died. And the sweet old dog, Penny, whose hair always drooped with matted knots, wasn't there one day, and Grandma said he'd run off.

Those moments, unpleasant as they were, never dominated. There was always something new ahead. I remember one particular Christmas Eve that still illumines my world today. After an evening of exchanging gifts with Grandma and Grandpa, our family piled into our station wagon, my mom hugging a bundled-up baby—one of my three little sisters, though I can't recall which one. The air was ice-cold, studded with bright stars, and the scent of evergreens filled the blue, blue night. At that moment I glanced up. Never had the stars seemed so bright. They bowed low, as if genuflecting in concert just for me. I could've touched them, I was sure of it, because when you are surrounded by love, heaven is closer. For a moment I held onto this sensation—only for a moment—but it was enough. I never forgot that moment. To me, heaven is still a little closer because of that night.

After many seasons of Sundays on the farm, I grew up as children do, and I went away to college. My grandpa died, my grandma moved to town, and the farm was sold out of the family. Only once since then, on April 3, 2009, have I stepped on that property again, when the owners invited us onto the land after catching us with cameras at the gate. My mom and I and a friend spent a few moments revisiting the dilapidated house, the tumbling barn, and my beloved pasture. It was a bittersweet day, but a good opportunity to bid farewell. Though I can no longer tread upon that property, I feel as if my soul owns part of the soil. And though I lost it, I am not sorry that I grew to love it.

Figuratively I've skated up Sugar Creek to Springfield, to other cities, to the place I am today. And now, having experienced life in a larger world, sometimes I want to skate back to the place where life was simpler and where someone else made the decisions about rusted metal and cow carcasses.

Though I cannot skate back to those wonderful days, the priceless treasure I collected on the farm sustains me today. On the farm, a renewable supply of promise always outpaced the unknown. Without realizing it, I had picked up that promise and stored it in my pocket much like Grandma's arrowhead. Today, when life gets noisy and complicated, I pull out the promise and remind myself that the cows are not always as dangerous as they seem, the spring flowers will bloom again, and untold joys are still waiting for me in Grandpa's pasture.